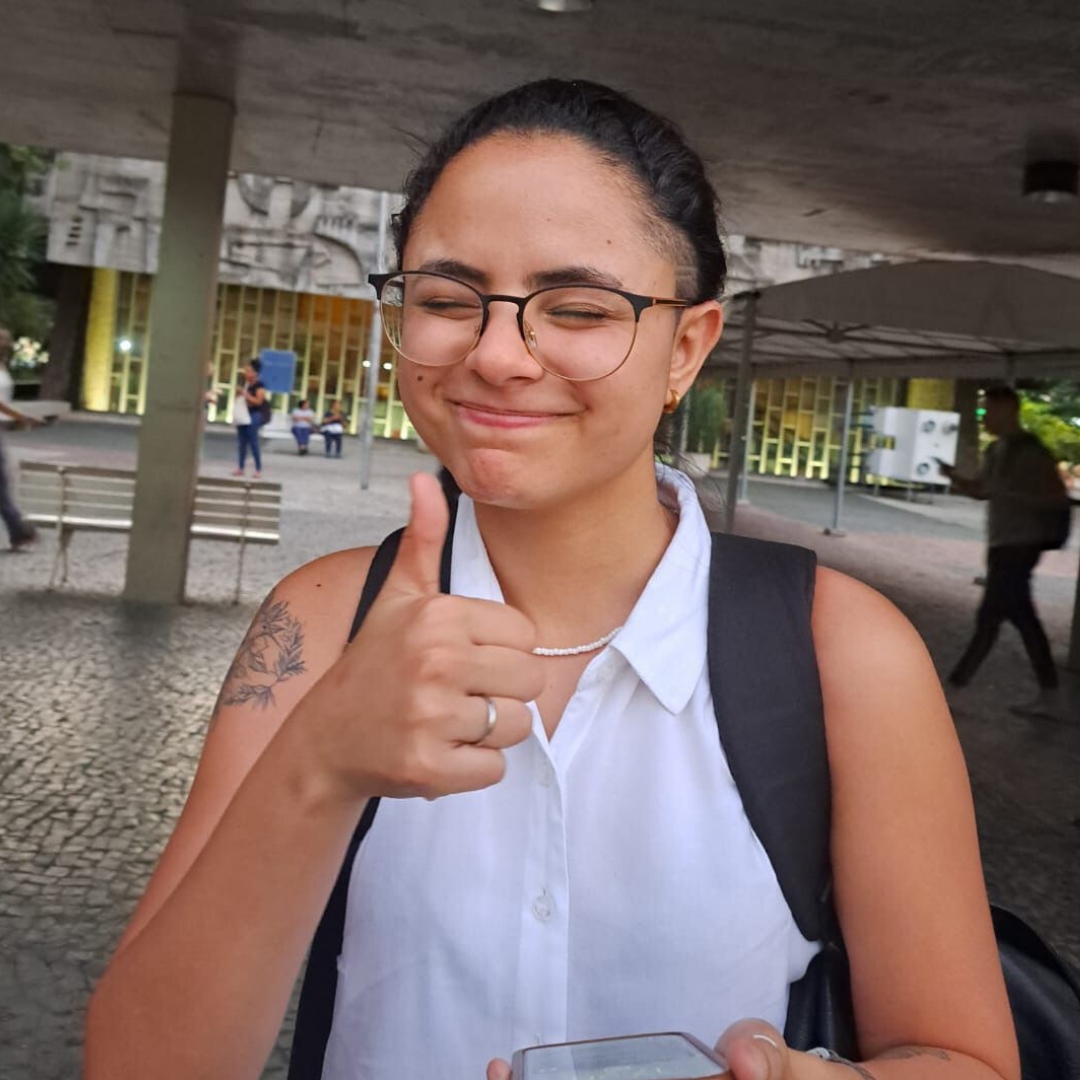

“Desculpa, professora!”, ela disse após me entregar a prova, preocupada com a extensão do texto. Era um ensaio de seis páginas em papel almaço (escrito ao longo de dois tempos de aula!) sobre Aurora Leigh. Eu disse para ela que não havia o que desculpar: estava ansiosa para ler o trabalho. E era verdade. Dentre provas, seminários e trabalhos de pesquisa, ao longo dos dois semestres em que fui professora dela nunca houve uma submissão da Fernanda que não fosse excepcional. Quando ficou sabendo que as inscrições para a monitoria do Encontro Literatura Inglesa Brasil estavam abertas, ela logo quis participar. Fernanda era assim: presente, participativa, generosa. Ela alegrava a sala de aula, sempre tinha um comentário pertinente, um paralelo a traçar, uma perspectiva crítica a trazer. Uma aluna que não apenas correspondia às expectativas: ela as excedia. Fernanda já era uma pesquisadora brilhante.

Neste sábado nós perdemos uma pessoa maravilhosa. Fernanda Carvalho era parte essencial do que faz do Instituto de Letras da UERJ um lugar especial. Sem sombra de dúvida, ela melhorava a vida de todos que a conheciam. Na sexta-feira, encerrei a resposta a um e-mail dela assim: “Você tem um futuro brilhante pela frente no caminho que escolher trilhar na vida acadêmica e além.” – Posso dizer que essa é uma certeza que era compartilhada não apenas por todos os meus colegas que tiveram o prazer de lecionar para Fernanda, mas também por todos que a conheciam.

Já com muita saudade, hoje nós publicamos esse texto in memoriam. Fernanda fez a submissão no dia 21 de junho de 2023. O ensaio dela estava programado para encerrar nossa série sobre North and South, um romance do qual eu sei que ela gostou muito. Muito obrigada, Fernanda.

– Marcela

***

Margaret’s Character: from a Romantic to a Realistic Perspective

Fernanda Carvalho

In some letters she exchanged with Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell frequently referred to her novel as either “Margaret” or “Margaret Hale”. It was the author of Hard Times who suggested the significant change to North and South. While he saw the center of the novel as the economic and cultural divisions between the South of England, traditionally a seat of power, and the North, which embraced manufacturing, Gaskell looked at her work through the development of her main character, Margaret. Directly “invested in the concrete examples of change […] that quotidian life provided” (CHILDERS, 2018, p.77), the author depicted social change as personal change without dissolving the story either into an industrial novel or into a love story. North and South is, thus, a novel of a character that forms itself not only in contact with the world but also by her internal philosophy. Being a participant rather than a mere mediator in the novel’s conflicts and disruptions, she experiences the disordering of her time through her mobility. She seems, thus, to be a portrait of this period of fundamental change, from feudalism to the rise of industrial manufacturing, from the set of romantic stories embedded in the South to the rise of “serious” social novels in the North. Establishing the principle that is the “natural combination of character with circumstances” (CHILDERS, 2018, p. 412) that leads Margaret to her development, it is the aim of this paper to observe Margaret’s evolution from a romantic to a realistic perspective through four main narrative bifurcations: her move to the North, Mrs. Hale death, the final demise of all her family and the business marriage with Thornton.

In the first pages of the novel, the reader is introduced to what appears to be another of Jane Austen’s plots: in an indulgent upper-class setting, Margaret and Edith are concerned about fairly standard topics for women of a fashionable London neighborhood in the Victorian Era. After her cousin’s wedding, Margert must come back to her family home in Helstone, which she describes with a picture-perfect rural scene: “Helstone is like a village in a poem—in one of Tennyson’s poems.” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 11). This romantic description of the place shows the mystique and idealistic outlook Margaret had that has to be taken down for her to align with the realistic logic of her period. She soon discovers that her memories of her father do not align with his present self, and not everything is as she remembered. Her lofty expectations are drowned in one of the first significant bifurcations of the book: Margaret’s father decides to leave the church and move to the North.

As the church was aligned with the gentry class wise, this movement furthermore symbolizes her immersion in the new reality. In this sense, some of her concepts, such as that of “shoppy people” – “I’m sure you don’t want me to admire butchers and bakers, and candlestick-makers, do you, mamma?” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 10) – and of manufacturers – “What in the world do manufacturers want with the classics, or literature, or the accomplishments of a gentleman?” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 24) – will turn ironic in the light of the people she will socialize with, admire and even defend later in the story. It is possible to see, thus, that her disdain of the North is entirely based, in this first moment, on her old class values and not on personal experience. To her, northerners seem far more pressed by the needs of the moment and less open to the beauty and enjoyment of arts compared to the South. The environment is described as characterless and unvarying, and her senses are overwhelmed with the industry-dominated life in Milton. The South, for her, brings the memories of this romantic past, while North does not seem to be open to this.

As Margaret spends more time among Milton’s masses, she starts to notice individuals more, which even leads her to assist a young woman in need, opening the door to a genuine friendship. Her identification with Bessy is only possible because Margaret starts to be open to realism, to the experiences in the North that diverges from her romantic past. When talking to her friend about her home, besides describing the shade of the trees, the birdsong, and its beauty, she remembers that “other people were hard at work in some distant place, while I just sat on the heather and did nothing” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 68). This simple statement symbolizes the change of perspective that Margaret develops when thinking of Helstone again: she is not only concerned with the romantic view of that beautiful place but also about its structure of labour. Her opinion about these relationships also begins to arise when she attends a dinner in Thornton’s house and compares the “the used-up style” of London parties with the North’s refreshing “desperate earnest” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 113). Knowledgeable enough to make a new judgment after hearing the perspectives of both Higgins and Thornton about the strike, Margaret states that she does not dismiss the “tradesmen” anymore and contrasts it with the superficiality of the Southern gentry and middle classes. Miss Hale stops, in this sense, idealizing both sides as a main character that comes to an understanding about herself, partially because of the knowledge she gained about the social whole (CHILDERS, 2018, p. 81). She will later acknowledge that “each mode of life produces its own trials and its own temptations” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 212), a nuanced view that was broadened by firsthand experience.

While the city offers a fresh air of reality for Margaret, its environment poisons Mrs. Hale. When Margaret faces her mother’s death, she sees everything else as trivial and reminisces about the quieter days that are not going to come back as she is now definitely inserted in the logic of realism. She goes from the detachment of reality to her conformation to it by embracing this second bifurcation of the book. Wishing to go back to the monotonous days of the previous winter, the character realizes the maturity she will have to gain besides coexisting with all sorts of people and experiencing cultural shocks.

Following the narrative, when a crowd of workers lets loose in angry hooting at Thornton’s door, Margaret tosses her arms protectively around him. This scene symbolizes, more than a lover’s initiative, her maturity in understanding her feelings and the critical thinking she has been developing. Thus, her action has more to do with her own unique blend of strength, courage, and realistic traits than an attempt to induce a proposal. That is reinforced by her later action of stepping in the doorway for Higgins not to go out drinking after Bessy’s death, indicating another moment in which she placed herself in harm’s way even when there wasn’t a romantic attachment. Moreover, when Thornton proposes, Margaret icily responds that his speech was “blasphemous [..] your whole manner offends me” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 137). The attribution of a romantic perspective to her act degrades it. Escaping to the country, a place more fitting for the romantic roots of Margaret rather than Thornton himself, he acknowledges that “there never was, never could be, anyone like Margaret” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 146). This conclusion shows that the character has changed: not being a representative of romanticism anymore, but not an entirely realistic individual either, she escapes his or anyone’s categorization.

Proving to have enormous consequences for Margaret’s development as a more complex character, her witnessing of Frederick’s escape changes the whole course of the narrative. Inquired by the police, Margaret instinctively lies to protect her brother, as she has no way of knowing whether he was safe out of England. This lie establishes her human side as a tangible and round character, and more than lying, it enables her to soon experience another human sentiment: guilt. Her development since she moved to Milton has not been, however, without a generous cost, and she acknowledges how great and long had been the pressure on her time and her spirits.

As soon as her father leaves for Oxford on a trip, Margaret finally enjoys a break from the relentless responsibilities that her role demands. Having continually sacrificed her own emotions for the well-being of others, now, at last, she has the luxury of examining her grief and feeling most keenly the lie she told. A character that has always been marked by pride now beings to emphasize the cultivation of humility as well. With the later death of Mr. Hale, Margaret’s last link with her family and with romanticism comes to an end. Life in London continues to be “surfeited of the eventless ease in which no struggle or endeavor was required” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 264), and Margaret, without a family to support, gradually resumes her old role of attending to Edith’s needs. Yet, in inserting the Helstone interlude (when Mr. Bell invites Margaret to visit her old home) in a late revision for the novel’s publication in book format Gaskell draws together Margaret’s past with her present and future. As she wanders the streets of Helstone, visits the parsonage where she had been raised, and confronts for the first time the cruel superstitions of her former neighbors, Margaret understands that she no longer belongs there. The journey towards Helstone hints at the complex nature of change and closes the cycle as the reader, along with the only Hale left, sees that Helstone has always been to her a wistfully mythical place associated more closely with idyllic pastoral romance than with the realities of nineteenth-century life. The “old picturesqueness, the old gloom, and the grassy wayside of former days” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 280) that blinded Margaret now fades away for the rise of the truth and the real. Hence,

the function of the South is not to provide a contrast with the industrial North but to be itself the subject of changing perspectives. When Margaret and Mr. Bell return to visit Helstone near the end of the novel, the point about change there is quite obviously recorded (Bodenheimer, 1979, p. 284).

The opposing reactions of Margaret and the Shaws over Mr. Bell’s death mark this statement: while Edith and Aunt Shaw react in stereotypically feminine ways to their proximity to death, Margaret immediately acts. Thus, Margaret’s change is also reflected through others, especially the ones she knew before life in Milton, who stayed stagnant and ignorant while she transformed along with the events of the novel.

After returning from the seaside, Margaret takes “her life into her own hands” (GASKELL, 1994, p. 295) as an heiress and a thoroughly realistic character who is complex enough to set her own path. Her entire social and psychological orientation must change to end with the final bifurcation of the novel: her proposal as a business meeting to Thornton. Although both characters must change to enter this resolution, as a woman, Margaret can only accept Thornton when she becomes an independent, self-reliant, and fully realized character, just as Aurora Leigh in Elizabeth Barrett-Browning’s verse novel. In this sense, her trajectory from always becoming second to someone else, subject to the demands of others, to the final conquering of her autonomy and freedom is shaped by the domestic calamities that constructed the plot. Thus, Margaret finally allows herself to set aside the burdens of her romantic past and live with resolve for a realistic future.

REFERENCES

BODENHEIMER, Rosemarie. “North and South: A Permanent State of Change.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, Vol. 34. No. 3 (Dec. 1979): 281-301. Pdf.

CHILDERS, J. Industrial Culture and the Victorian Novel. The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel. Cambridge University Press, 2018. (p. 77-96).

CHILDERS, J. Victorian Theories of the Novel. The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel. Cambridge University Press, 2018. (p. 406-423).

GASKELL, Elizabeth. North and South. London: Penguin Books, 1994. Print.